Digest This…

Endurance athletes require nutrition precision.

Nutrition guidelines for the mainstream do not apply to the rigorous exertion, tireless effort, and inexpressible demands of endurance athletes. Nutritive decisions impact every aspect of training, performance, and recovery.

Balancing macronutrient partitioning, micronutrient density, nutrient periodization, and other facets of the training for performance formula is paramount. The key is enhancing health and longevity in the process. Too many endurance athletes are fit yet unhealthy. Read about metabolic efficiency.

No better place to begin the nutrition discussion than the digestive process. Digestion technically begins with food preparation but instantly revs during mastication.

The digestive system – known also as the alimentary or the gastrointestinal [GI] tract – is responsible for fractionalizing, absorbing, and assimilating food. Find a simplified version of GI tract functions below:

The foods you ingest via your GI tract represent your inside link to the outer world. Your choices will either enhance or hinder your desired endurance outcomes. Your GI tract filters what enters your bloodstream and what is discarded.

Your immune system is profoundly impacted by the health of your microbiome. This will delineate the difference between effort and struggle in your endurance efforts, your health, and your longevity.

Mastication facilitates the lubrication of food as salivary glands provide enzymes to soften food and convert carbohydrates [CHO] to simple sugars. It is at this stage the pizza, apple, Snickers bar, or whatever you consumed becomes bolus.

Your tongue savors the sensations of the ingested food – bitterness, saltiness, sweetness, and the like – before swallowing the particulates. The epiglottis opens its trap door so to speak to allow food to be transported from the mouth to the stomach via the esophagus.

Your stomach secretes hydrochloric acid [HCI] to further pulverize the bolus. The harmonious interface between bolus and secretion is termed chyme.

Chyme represents a sizable chunk of food that will take hours to depart the stomach. The succulent Angus steak you consumed and fiber-rich foods represent a couple of examples that require much longer to digest, absorb, and assimilate in your body.

HCI is critical in the breakdown of proteins. CHOs have been the primary macronutrient disintegrated and digested to this point because the requisite enzymes for the digestion of protein and fat have not yet been secreted.

When the stomach has completed its digestion process it transports chyme into the small intestine.

The small intestine is labeled small not because of its length but because of its diameter. Its length is nearly 10 feet. The small intestine secretes enzymes to break down protein and fat before shuttling it to the large intestine.

The small bowel connects to the large bowel, also called the large intestine or colon. The intestines are responsible for breaking down food, absorbing its nutrients, and solidifying the waste. The small intestine is the longest part of the GI tract and it is where most of your digestion takes place.

The small intestine has a beginning section, a middle section, and an end section. Although there is no real separation between the parts, they do have slightly different characteristics and roles to play.

Serious digestion occurs in the small intestine [small bowel] such as the following:

→ Systematically breaks food down;

→ Absorbs nutrients;

→ Extracts water;

→ Shuttles food within the GI tract

The following components of the small intestine make it happen:

→ Duodenum;

→ Jejunum;

→ Ileum

Duodenum

The duodenum measures 10 inches long. It is the smallest of the small intestine sections. Most of the intestine handles the majority of the digestion. Consumed foods can park in the small intestine for three to 10 hours.

Your liver, gallbladder, and pancreas contribute digestive juices to help the small intestine break down food.

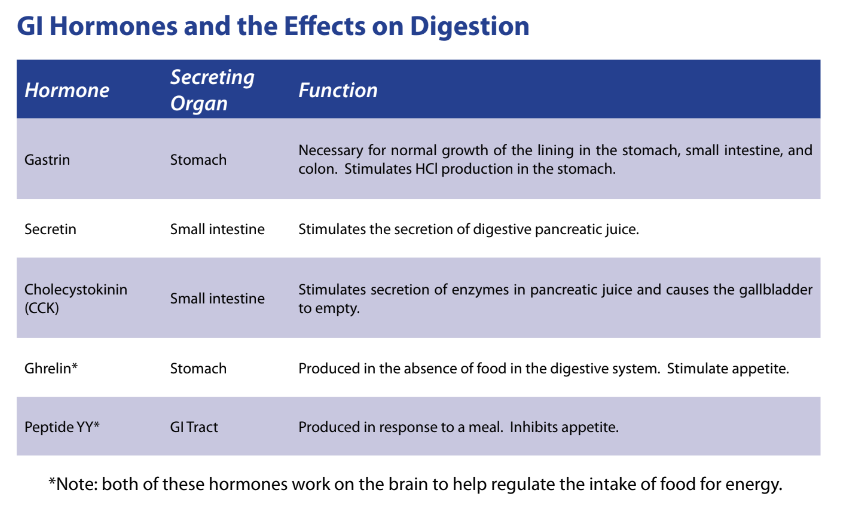

Ducts from these organs feed into the duodenum. Hormonal glands in the lining of the duodenum signal these organs to release their chemicals when food is present.

Jejunum

The jejunum measures approximately four feet while the ileum is approximately five feet. The jejunum partners with the duodenum to handle the majority of the digestive process.

The remaining small intestine lies in many coils inside the lower abdominal cavity. Its middle section [the jejunum] accounts for a little less than half of the remaining length. The volume of blood vessels gives the jejunum its deep red color.

After chemical digestion in the duodenum, food moves into the jejunum, where the muscle work of digestion kicks in high gear. Nerves in the intestinal walls trigger its muscles to churn food [segmentation] with digestive juices while other muscle movements keep the food moving forward.

Ileum

The ileum is the last and longest section of the small intestine. The walls of the small intestine begin to thin and narrow and the blood supply is reduced. Food spends the most time in the ileum where water and nutrients are absorbed.

Segmentation slows and peristalsis takes control by shuttling food waste to the large intestine. The ileocecal valve separates the ileum from the large intestine. Nerves and hormones signal the valve to open to let food pass through and close to keep bacteria out. Special immune cells line the ileum to protect against bacteria.

Peristalsis makes digestion a reality. It moves food and fluids through each stage of the digestive process. The slow, steady progress of peristalsis is important for digestive health. It gives your body time to break down food for digestion, absorption, and assimilation. It plays a vital role in flushing accumulated bacteria and waste products promptly.

The small intestine is where most of the long process of digestion takes place. The process can take nearly five hours.

Mucosa

The walls of the small intestine are lined with dense mucosa with many glands that both secrete and absorb. In the jejunum and the ileum, the mucosa secretes small amounts of digestive enzymes and lubricates mucus while absorbing nutrients from your food. Each section is designed to absorb different nutrients with water.

The thick mucosa has many folds and projections and its surface area is nearly 100 times as broad as the surface area of your skin. This is why 95% of the CHOs and protein you consume are absorbed in the small intestine. It absorbs about 90% of the water that it receives during digestion. The rest will be absorbed in your large intestine.

Plant foods enhance small intestine health. Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains provide your bowels with adequate fiber. Fiber helps feed the good bacteria in your gut and sweep out toxins. Fiber will make you crave water which is a good thing. Fiber and water keep bowel movements regular which flush toxins from your body.

Most fruits and vegetables are also alkalizing which helps balance out the acidic Western diet. High acid content can erode the protective mucus in the gut. Many other Western foods and lifestyle habits are acidic – including processed foods, meat and dairy products, caffeine, and alcohol. We could all benefit from more alkaline foods in our diet.

The large intestine is approximately three and a half feet long. Little digestion is performed in the large intestine – even though it is divided into five sections:

→ Cecum;

→ Ascending colon;

→ Traverse colon;

→ Descending colon;

→ Sigmoid colon

The large intestine acts as a storage facility. Sodium, potassium, and water are absorbed in the large intestine. Digested residue hangs in the large intestine for about 72 hours before excretion via fecal matter.

When you understand how your body processes the timing and ingestion of macronutrients, micronutrients, and supplements in conjunction with your sleep habits, heart rate variability, blood analysis, and biological age you will begin to comprehend your limitless potential in life and sport.

A healthy GI tract means a happy endurance athlete.

We have the technology to eliminate the guesswork, decode superhuman, reverse biological aging, and propel your limitless potential.

Epigenetics represents an unprecedented, bold, medical paradigm leveraging cutting-edge technology to shift genetic expression to create mind-blowing results in life and sport.

A limitless life is a choice…

Click Performance Medicine™ to ignite your limitless genetic potential in life and sport.

Sources:

* Christopher R. Mohr, PhD, RD, CSSD

Mohr Results

* National Endurance Sports Training Association

Pingback: Epigenetics – SYNERGY™